Voices of Deities AMI

An essay by Simon O’Dwyer with contributions from Dr. John Purser, Dr. Eamonn Kelly and Dr. Peter Holmes.

History, oral stories from earlier centuries and archaeological remains tell us of a religion in Ireland and parts of Britain that was practiced for thousands of years before the introduction of Christianity. While many gods, goddesses and intermediaries are described and named, the essential core of religious belief was, on the one hand, the Sun god who was male and on the other the Earth goddess being female. It was important that these two would exist in harmony to ensure a continuing wellbeing for the people. It is possible to look at early evidence of the pairing of deities by examining the great buildings from the Neolithic period 6,000 to 4,500 years ago. Many of these megaliths are aligned to facilitate the observation of interactive movements between the sun star and its planets. Among the oldest and most famous is the great temple observatory of Newgrange. It is one of a number of structures situated in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Brú na Bóinne, Co. Meath, Ireland.

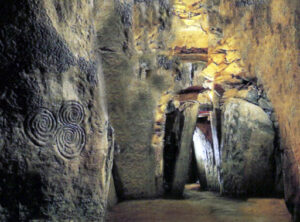

Newgrange – central chamber. Brú na Bóinne, Co. Meath, Ireland.

This building is specifically positioned and designed to allow for the physical realisation of the exact moment in earth’s orbit around the sun when the winter days cease to shorten. A new year is born on the 22nd December as the dawn begins seconds earlier than the previous one. A beam of sunlight enters along the building’s main passage and illuminates a central chamber containing a stone carved with a triple spiral. We know that the culture which evolved and created these advanced buildings was that of a farming society which was centered on the keeping of cattle.

Later, some 3,000 years ago cast bronze horns and trumpets began to appear throughout Ireland and in parts of Britain. They occurred in pairs or multiples of pairs. A pair consisted of a conical horn, it’s shape clearly derived from cattle horns with a mouthpiece in the side. The second one was fitted with a cylindrical tube extension and the mouthpiece on the end so that it became a trumpet. Over one hundred examples survive from Ireland and a couple from Britain. They occur in a variety of sizes and designs which appear to be related to the geographical area where they originate.

In 2006 at the International Study Group of Music Archaeology Conference in Berlin, Dr Peter Holmes proposed that the differences in the pairs could be explained by the side-blown horns being female and the end-blown trumpets being male. He has also established that a very advanced level of bronze casting was achieved to make beautifully designed and crafted musical instruments. In looking for clues as to their function, it is important to derive the nature of the animal horn examples which must have preceded the bronze. To do this we acquired a pair of horns that came from a young Scottish Highland Celtic steer. They were given to us by Dr John Purser from his croft on the Isle of Skye. John observed that, ‘the ancestry of these cattle can be traced back to the Neolithic period. The bulls grow horns straight out on each side of the head whilst the cows grow them out and then they twist either forwards or backwards. Thus, the bull horns are on two planes whilst those of the cows are on three.’

We know that all the horns and trumpets of Ireland and Britain in this family are on two planes indicating the likelihood that the designs have their origins specifically in bull horns. It is interesting to note that the lur which are Bronze Age instruments from Scandinavia are designed on three planes, so perhaps they are derived from cow horns.

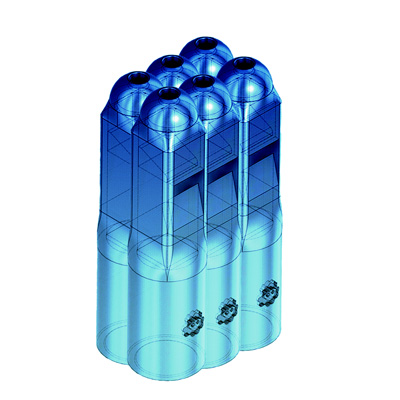

Instruments made from steer horns shown here with cast Bronze Age reproductions (originals from Co. Antrim), adharc (above) and dord árd (below).

Using the ‘Skye pair’, it was a relatively simple matter to cut an oval mouthpiece opening into one and add an extension tube made of wood to the end of the other. Both turned out to be sweet-sounding musical instruments. Knowing that the bronze family began to appear 3,000 years ago, it begs the question as to how much earlier the first animal pairs emerged and why subsequently were they ritualised using a rare and expensive metal? Over thirty years, our research has established that surviving complete instruments and reproductions thereof allow for the playing of tone alteration and instrumental overtone using circular breathing. The open nature of the mouthpieces and the absence of a choke means that the player may create higher notes over a continuing fundamental in a manner similar to the overtone singing techniques used in Tuva, Nepal and Tibet. Dr Eamon Kelly has contributed to this essay as follows, ‘these horns and trumpets were played as pairs at the inauguration of kings. An important part of the ceremony was the bringing together of the Sun god and the Earth goddess so that crops would grow, animals would get fat and the well being of the people would be ensured.’

Given the male/female make-up of the deities, the proposal that a horn/trumpet pair were also male and female and the undoubted importance of these instruments may suggest that they were made to represent the god and goddess. The specific designs which allow for the use of instrumental overtone might have been incorporated into the sound so that eerie, other worldly music was played representing the voices of the deities. Thus, the huge investment into creating such magnificent and advanced bronze and wooden horns and trumpets could be explained. We know that pre-Christian Ireland and Britain were populated by many kingdoms. If they all required instruments to inaugurate a new king or queen for a religious and political purpose, that would be a solid reason to have them made throughout the culture. Though designs appear to have been localised, there is an extensive variety of sizes, shapes and decoration.

The Bronze Age ended circa 2,600 years ago with the introduction of iron, yet the use of beaten bronze and fine riveting that had emerged continued to develop. Instruments evolved and became longer and lighter. Side-blown horns disappeared in favour of trumpets. The oldest known example of an end-blown long trumpet is from Killyfaddy, Co. Tyrone and is made in sections of yew wood. While not complete, the four tubes when assembled indicate the instrument was approximately 3 meters long and carbon dating puts it at 2,300 years old. Through comparison with the later bronze examples the likelihood is that it was played in an ‘S’ position held vertically in the air by a bearer using a long pole in front of the player. In this way there would be a dramatic visual impact and the trumpet could be played in a standing or walking mode.

An Trumpa Fáda, (Ardbrin trumpet).

Approximately 150 years later, sheet bronze trumpets of a similar design emerged. The longest of these is from Ardbrin, Co. Down. A complete trumpet survives plus the conical part of a second instrument. It is possible through examining the wear on the complete one to establish that these instruments were also presented with the bearer in front and the player behind. Yet, other surviving examples of Iron Age trumpets including the Loughnashade (Co. Armagh), Roscrea (Co. Tipperary) and Llyn Cerrig Bach (Anglesey) are fashioned with very thin beaten bronze and are clearly made to be held up and played by one person. The Loughnashade may be assembled either as a ‘C’ semicircle or as an ‘S’ sigmoid curve. The other two examples play best in the ‘C’ semicircle assemblage.

An Trumpa Mór – pair – reconstructed – Roscrea (Co. Tipperary) and Llyn Cerrig Bach (Anglesey) being played as part of the World of Stonehenge Exhibition at the British Museum 2022.

When a reproduction pair are held up together in the ‘C’ position with the musicians ‘back-to-back’, the audience are presented with a full circle. It is probable that the primary function of the Iron Age trumpets was to bring together the Sun god and the Earth goddess in the same way as their Bronze Age predecessors. However, there are descriptions in legends from the period, of numbers being played in parade and as a part of a healing ceremony. These magnificent trumpets were at the peak of the pre-Christian religion and culture which had its origins some 4,000 years earlier, yet their demise was about to be realised with the arrival of the first Christians 1,600 years ago.

More recently, some 1,300 years ago, a book of psalms was written in Kent, England. One of the illuminations depicts a religious/musical scene involving musicians and dancers. Two of these are playing conical, straight horns made from yew wood, decorated with sheet bronze bands and fitted with a cast bronze mouthpiece. We know this because an original was removed from the bank of the River Erne, Co. Fermanagh in 1956. It is a rare example of an Early Medieval musical instrument existing today alongside an illumination showing a pair being played in their own context. It may be that these horns are the final manifestation of the pre-Christian era. Perhaps, the voices of the god and goddess are included in the image by sharing the music with that of the trinity.

Psalter horns – reproductions of the River Erne horn. Played here by Malachy Frame and Simon O’Dwyer with Barnaby Brown on lyre. Featuring the Vespasian Psalter illumination behind. 2016.

Conclusion

It is likely that the development of particular horn and trumpet designs indicates that they are members of a single unbroken family. All are similar, being either conical or part cylindrical, they feature an open mouthpiece design which facilitates the use of circular breathing, tone alteration and the creation of overtones. All these instruments are shaped and made by master craftspeople who were using the most advanced metal and wood technology of their time. All complete original examples and the new reproductions possess complex musical qualities that would only have been possible if the makers had an extensive and comprehensive knowledge of the nature of musical law. All the horns and trumpets would appear to have their origins only in Ireland and Britain. Manufacturing ideas such as the use of lost wax (cire-perdue) for casting which were incorporated from mainland Europe may have replaced the indigenous dry clay methods. Yet the royal, religious practices that begat the family appear to be specifically Irish/British as do casting methods and the use of fine riveting.

Maintaining the balance between male and female, the earth and the sun, death and birth; this was a farming religion, that also incorporated the most advanced science and knowledge of the time. While the culture changed along with the evolution from stone into metal, the core belief did not. Down through thousands of years, horns and trumpets were made from cattle horns, cast bronze, sheet bronze and lastly from yew wood. The musical instruments would continue to fulfil the same essential function as ‘voices of deities’ until the final end that was Christianity, when they would be silenced.

Many of the Irish/British instruments from both the Bronze and Iron Ages were recovered from either water pools or from where water pools had once been. They are usually very worn and sometimes with evidence of repair, indicating that they had endured a long musical playing life. A pool could be considered common to both the Sun god and the Earth goddess as the water that kept it full came from the sky as rain and from the earth in the form of a natural spring. If the horns and trumpets were perceived as being the voices of deities, by depositing them in a pool would, in effect, be returning them to their owners, their function then being handed on to a new pair. Thus, the offering could be an act of celebration, respect and gratitude to the deities for their beautiful voices, for life and the sacred gift of water that sustained it.

Many thanks to Dr. John Purser, Dr. Eamonn Kelly, Dr. Peter Holmes and Maria Cullen O’Dwyer. – January 2023.